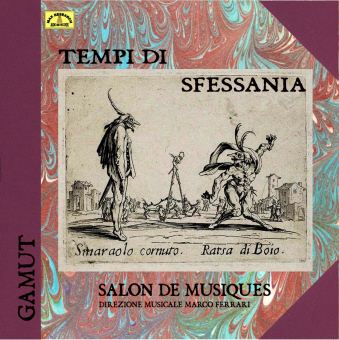

Tempi Di Sfessania – Salon De Musique (DL027)

Title: Tempi Di Sfessania

Performer: Salon De Musique

| ||

|---|---|---|

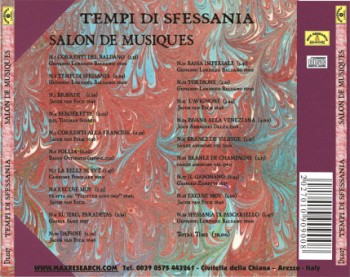

Tracklist:

N°1 CORRENTI DEL BALDANO

tratte da: “Intavolatura per sonar sopra le sordelline” 1600, Giovanni Lorenzo Baldano:

questo manoscritto, estremamente simile alle stampe per chitarra barocca posteriori di una decina d’anni, inaugura un tipo di raccolta in cui compaiono musiche non polifoniche ma “armonizzate”; se nelle stampe per chitarra barocca non venne riportata la melodia (evidentemente archetipica e universalmente nota) ma solo l’impianto ritmico-armonico, in questo caso avviene il contrario: Baldano riporta la melodia per uno strumento popolaresco come la sordellina (piccola zampogna in uso tra i nobili) che lascia intuire la tessitura armonica delle melodie.

N°2 TEMPI DI SFESSANIA

tratti da: “Intavolatura per sonar sopra le sordelline” 1600, Giovanni Lorenzo Baldano:

raro esempio di melodia per la danza “sfessanìa”, che farebbe pensare ad una danza lenta e statica piuttosto che alla progenitrice della tarantella, come si é voluto da più parti sostenere. Questa danza fu sicuramente nel repertorio della Commedia dell’arte come testimoniano le formidabili stampe di J.Callot.

N°3 – 4 BRAVADE ET BERGERETTE

tratti da: “Fluyten lust-hof” 1646, Jacob van Eyck: “Bravade” e “Danserye” 1551, Tielman Susato: “Bergerette”:

Van Eyck flautista e “carilloneur” cieco, fu pagato dai concittadini di Utrecht, per suonare danze ed arie; le sue esecuzioni furono tanto apprezzate sia per il virtuosismo che ancora oggi traspare dalla raccolta a stampa come per le melodie che scelse anche dal repertorio francese di più grande diffusione all’epoca.

“Bergerette”, tipica composizione in stile colto polifonico su di una melodia (al soprano) che al contrario, mostra tutte le caratteristiche della tradizione orale.

N°5 CORRENTI ALLA FRANCESE

tratte da: “Fluyten lust-hof” 1646, Jacob van Eyck; “La volette”, “De france courante”.

N° 6 FOLLIA

celeberrimo basso armonizzato che compare forse per la prima volta in “Oy comamos y bebamos” di Juan del Encina (1469-c.1530). Ne abbiamo scelta come melodia per danza, la versione nota alla fine del 600′, per una serie di improvvisazioni che sovrappongono suddivisioni ritmico melodiche su 2-3-4-6-8 tempi e si succedono con tre episodi diversi in rapporto proporzionale.

N°7 – 8 LA BELLE SE SIT ET EXCUSE MOY

tratti da: manoscritto “BU 2216″ e “Fluyten lust-hof” 1646, Jacob van Eyck:

“La belle se sit” é una antica canzone che dà inizio al tema popolare della donna che muore per amore e condivide la tomba del proprio amato: arriva ai nostri giorni in un gran numero di canzoni in tutta la cultura tradizionale europea. In Italia é nota anche come “la bella Cecilia” che farebbe pensare ad una malintesa interpretazione orale e fonetica del titolo francese.

N°9 RUJERO, PARADETAS

tratti da “Instrucciòn de mùsica sobre la guitarra espanola” 1697, Gaspar Sanz:

melodia celeberrima fin dall’inizio del 600′; notevolissimo il fatto che sia stato possibile ascoltarla praticamente identica, nella musica popolare per violino dell’appennino bolognese fino agli anni 70′ del 900′.

N°10 DAPHNE

tratta da: “Fluyten lust-hof” 1646, Jacob van Eyck.

N°11 BASSA IMPERIALE

tratta da: “Intavolatura per sonar sopra le sordelline” 1600, Giovanni Lorenzo Baldano:

questa melodia, notissima nel 600′, sembra discendere dalle “Padoane alla veneziana” di J.A. Dalza.

N°12 TORDIONE

tratta da: “Intavolatura per sonar sopra le sordelline” 1600, Giovanni Lorenzo Baldano.

N°13 L’AVIGNONE

tratte da: “Fluyten lust-hof” 1646, Jacob van Eyck; “Lavignone” e “Courante I”

N°14 PAVANA ALLA VENEZIANA

tratta da: “Intabulatura de lauto “ 1508, Joan Ambrosio Dalza:

di questo tema Dalza fornisce quattro versioni diverse, lasciandoci pensare che si trattasse di una melodia archetipica per la pavana.

N°15 -16 BRANLE DE VILAYGE e BRANLE DE CHAMPAGNE

danze anonime del 500′.

N°17 IL GABONANO

tratto da: “Il Scolaro” 1645, Gasparo Zanetti; “La montagnura, Il Gabonano, La ballorìa”:

serie di danze che suggeriscono stretti rapporti con il teatro (il Gabonano fu un personaggio della commedia dell’arte) e con la musica di tradizione orale; (La Montagnura venne trascritta da Zanetti con un ritmo ed un incipit che fanno pensare ad un tema popolare preesistente).

N°18 EXCUSE MOY

tratta da: “Fluyten lust-hof” 1646, Jacob van Eyck.

N°19 SFESSANIA DI PASCARIELLO

tratta da: “Intavolatura per sonar sopra le sordelline” 1600, Giovanni Lorenzo Baldano.

Salon de Musique

Marco Ferrari: flauti, cornamuse e fagotto

Giorgio Pinai: flauti traversi seicenteschi

Alessandro Urso: violino barocco

Fabrizio Lepri: viole da gamba e violoncello barocco

Elisabetta Benfenati: chitarre rinascimentali e barocche

Luca D’Amore: tiorba

Massimiliano Dragoni: percussioni

Brevi note sulla registrazione

Grande cura è stata riposta nel riprendere l’evento con le emozioni della performace live.

I microfoni dedicati alla ripresa dell’ambienza sono stati dosati per ricreare le dimensioni del luogo di ripresa, mentre i microfoni dedicati ai musicisti hanno permesso la precisa localizzazione degli strumenti.

L’ensemble è collocato a circa 3 / 4 metri del punto di ascolto, in un semicerchio virtuale. Alle loro spalle e intorno all’ascoltatore si percepisce il riverbero ampio e presente della chiesa romanica luogo di ripresa. Gli strumenti sono ben riconoscibili, ognuno con la propria timbrica e spaziati secondo le originali proporzioni.

Se il sistema di ascolto lo permette, si percepiscono le reali dimensioni e altezze degli strumenti. La cura maggiore comunque è stata posta nel catturare le emozioni che i musicisti suscitavano durante l’esecuzione e riproporle nella nostra sala, per goderne appieno durante l’ascolto.

Buon divertimento a tutti.

Buon ascolto

Massimo Piantini

Brief notes on the recording

Great care has been put into the recording of the event with the emotion of the live performance.

The microphones dedicated to the recording were balanced to recreate the dimensions of the location of the recording, while the microphones dedicated to the musicians allowed the precise location of the instruments.

The ensemble is placed 3/4 meters from the listening point. In a virtual semicircle behind and around the listener one can percieve the ample reverberation present in the Romanic church recorded in. The instruments are recognizable, each with its own timber and spaced according to the original proportions.

If the listening system allows it, the real dimentions and heights of the instruments are percieved. Most of the attention was put into capturing the emotions which the musicians were giving during the performance and reproposing them in the studio to fully enjoy them during the listening.

Enjoy the concert

Massimo Piantini

Ascolta un sample - Listen a sample

Ornamentazione ed improvvisazione strumentale tra 500′ e 600′.

Tutti i brani di questo disco sono ascrivibili a quel tipo di musica strumentale per danza che iniziò a lasciare le prime tracce alla fine del 400′ nella intavolatura per liuto di Pesaro, in quelle di J.A.Dalza e in diverse altre; di Castello Arquato per organo e di Antonio Gardane per cembalo nel 500′, fino ad arrivare un secolo dopo, alle prime stampe con alfabeto per chitarra barocca: questo repertorio si differenzia dalla ben più nota polifonia strumentale per danza (Phalese, Susato e i moltissimi altri.), poiché i suoi brani sono concepiti come semplici melodie con accordi in accompagnamento, senza alcuna preoccupazione di condotta polifonica; si tratta in sostanza di semplici “canovacci” musicali (concettualmente simili a quelli teatrali della commedia dell’arte) che presuppongono una ampia parte di pratica improvvisativa ed estemporanea.

Si potrebbe ipotizzare che le fonti suddette, considerate minori per la apparente pochezza musicale rispetto alle colte fonti polifoniche coeve, siano una piccola traccia cartacea dell’enorme attività che avveniva nel mondo dei musici pratici o soltanto orecchianti.

Abbiamo scelto di scomporre e filtrare queste musiche attraverso l’esecuzione a memoria, isolando le melodie dalle sovrastrutture di scrittura o polifoniche (quando presenti); dopo aver appreso mnemonicamente le “impalcature” melodiche dei brani, le abbiamo rese di volta in volta diverse (senza alterare o nascondere la melodia come avviene praticando la “diminuzione” colta), attraverso l’uso di una ornamentazione applicata in modo estemporaneo e suggerita dalla struttura musicale, interpretando inoltre per i diversi strumenti, i ruoli tipici della musica di tradizione orale: melodia, basso, armonia e ritmo. Non ci siamo voluti sostituire ai musicisti ed ai compositori del passato che furono evidentemente il livello più alto d’espressione della propria arte, ma cerchiamo di relativizzare lo stile della musica colta scritta, unico ad esserci pervenuto, con una riflessione sulla tradizione non scritta che a ben vedere ed ascoltare ci parla ancora attraverso i canali più impensati della cultura odierna.

Chi si occupa di prassi esecutive della musica tradizionale, sa che esistono pratiche di accompagnamento ritmico-armonico improvvisato per il basso e gli accordi ed inoltre concetti estetico-tecnici che riguardano la pronuncia, l’articolazione e l’ornamentazione per gli strumenti melodici, comuni a gran parte dei repertori di musica strumentale di tradizione orale europea.

Chiunque abbia ascoltato uno strumento “tradizionale” (a fiato, a corda o a tastiera), sa quale maestria raggiungano i musicisti nella articolazione ottenuta con l’ornamentazione; e questo (con similitudini impressionanti) dalla Sardegna alla Bretagna, dalla Romania all’Irlanda; nella tradizione orale non potrebbe mai esistere una melodia scevra di ornamentazione continuamente cangiante, senza formule ornamentali di attacco, passaggio ed articolazione che ne sottolineino ed arricchiscano i tratti; non potrebbe mai esistere una melodia la cui pronuncia fosse uniformata tra più strumenti, come succede nella musica composta e scritta.

Con questo CD tentiamo di individuare una piccola parte del repertorio al confine tra scrittura ed oralità, da cui la musica popolare urbana europea é stata ed é ancora tanto influenzata e di cui conserva tante tracce; esso fu veicolato nel mondo della musica popolare, non solo ma anche, dalle famose compagnie della “commedia”: questa ipotesi storica é anche un espediente per immaginare uno stile esecutivo originale, incentrando il repertorio sul flauto, lo strumento che nel 600′ venne definito (per il suo basso costo) il “violino dei poveri”.

La nostra illusione è che queste esecuzioni possano ben rappresentare il mondo dei musici pratici di teatro, giocolieri ed accademici allo stesso tempo, che per stupire o commuovere non avrebbero rinunciato agli espedienti del mestiere; essi sconfinarono dalle corti alle piazze, trasformarono i repertori, contribuendo a diffondere i contenuti e una pratica che influenzarono gran parte della musica per danza di tradizione orale e scritta, attraversando gran parte d’Europa.

Marco Ferrari

“Between written music and the oral tradition”

Ornamentation and instrumental improvisation in the 16th and 17th centuries.

All of the works featured in this recording belong to a style of instrumental music that begins to appear at the end of the 15th Century with the Pesaro lute manuscript and the works of J.A. Dalza, continuing with Castello Arquato’s organ pieces and Antonio Gardane’s harpsichord collections of the 1500′s, then going on for another century with the printing of the first lettered tablatures for baroque guitar. This music differs from more well-known polyphonic dance repertoire of the era – by composers such as Phalese and Susato, to name just two examples – because of how it is conceived: simple melodies with chordal accompaniment, unconcerned with the niceties of polyphonic voice-leading. It is made up, substantially, of simple musical “Canovacci:” a term used to designate the plot sketches used as a basis for improvisation by the actors of the Commedia dell’Arte. Indeed, these pieces are conceptually similar to the “Commedia,” because they call for many improvisational and extemporary elements.

One could even imagine that these sources, considered minor or unimportant because of their apparent lack of musical substance, especially when compared to the sophisticated polyphonic works of the same era, are only a small written trace of the enormous activity that took place in the universe of both formally trained and popular musicians the “eye cats” and the “ear cats” of the era.

We chose to deconstruct and filter this music by playing it by heart. We isolated the melodies from the written (or polyphonic, when applicable) structures, then memorizing this melodic “scaffolding.” The pieces were played differently each time by using an extemporaneous ornamentational style inspired by the musical structure, (without distorting or concealing the melody, as sometimes happens in the more sophisticated written diminutions,) moreover assigning the roles typical of music in the oral tradition – melody, bass, harmony and rhythm to each of the instruments. We never tried to take the place of the musicians or composers that have come before us: they were, of course, far superior in expressing themselves in what was their own idiom. We have simply tried to temper the style of written art music, the only kind that has come down to us, with a reflection that comes from the non-written traditions that still speak to us via the most unexpected channels of contemporary culture.

Whoever has studied and/or played traditional music knows that the players of bass and chordal instruments have developed a method of improvising rhythmic and harmonic accompaniment, while those who play melodic instrument follow certain aesthetic and technical concepts regarding articulation and ornamentation. These concepts and practices are shared by a great number of the instrumental repertoires found in the European oral tradition.

Anyone who has ever listened to the player of a “traditional” instrument – be it wind, string or keyboard – knows what level of articulation they are capable of reaching by using ornamentation. The same set of skills can be found (with almost shocking similarities) from Sardinia to Brittany, from Rumania to Ireland. In the oral tradition, it is inconceivable to have a melody bereft of continually varying ornaments, or one without a decorative formula for every attack, passage or articulation, underlining and enriching its features. Nor could there be a case where a melody is expressed in the same way by different instruments, as is common in written musical composition.

With this recording, we feature a small part of a repertoire that lives between the world of the written and the orally-transmitted, that has left many traces in the popular music of Europe’s urban centers, where it had and still has an enormous influence. A repertoire that was brought into the popular tradition by, among others, the famous theatrical companies of the “commedia.” This hypothesis also helps us to imagine a new way of performing early music, treating the melodies as part of the collective consciousness and centering the repertoire on the recorder, known as “the poor man’s violin” in the 1600′s because of its low cost.

Our hope is that this kind of performance practice could represent the world of the theatrical musicians of the era: simultaneously jugglers and scholars, using every of the trick of the trade to amaze their public or bring them to tears. Living between the courts and “piazze”, they transformed repertoires, and helped to spread the contents and the practice of a style that would influence much of the dance music in the written and oral traditions from all over Europe.

Marco Ferrari (traduzione di Avery Gosfield)

Ascolta un sample – Listen a sample

La musica e la commedia dell’arte

Con l’atto notarile di V. Fortuna, stipulato a Padova nel 1545, prima testimonianza di fondazione di una Compagnia di commedianti, abbiamo la possibilità di sostenere l’assunto secondo il quale l’attore e il musicista della Commedia dell’Arte fossero in verità la stessa persona e che, nell’uno e nell’altro caso, il virtuosismo annesso all’improvvisazione su tema, su canovaccio, fosse in qualche modo paritetica.

Tra gli attori citati, Fortuna indica Francesco da la Lira, musico-attore e danzerino. L’arcaico utilizzo dell’identificazione, a mo’ di “nome in arte”, dell’attore/musico e il suo strumento, fornisce la solida base per una ricerca storico-musicale interna alla Commedia dell’Arte; grazie ai nomi degli strumenti, infatti, non solo si recupera l’oggetto “strumento musicale” in quanto tale, ma, soprattutto, una tipologia d’estetica, di gusto e di caratterizzazione all’epoca della Commedia, quella commedia che nel 1643 F. Bertarelli definiva: “quel carnevale italiano mascherato, ove si veggono in figura varie inventione di capritii…”.

Come il documento notarile, così anche le famose immagini del Callot, in veste di documenti storici, vengono in aiuto a tale approccio. L’artista intitola la serie delle sue opere dedicate alle maschere del teatro a lui contemporaneo, “Balli di Sfessania”, 1621/22; la prima pagina si presta in maniera esemplare a connotare le osservazioni precedentemente evidenziate: tre personaggi, tre maschere su di un piccolo palcoscenico, in atto di danzare accompagnati da colascione e tamburello; tre elementi dunque, musica-teatro-danza, dai quali la Commedia stessa dipende.

Nella serie di figure e movimenti rappresentati, il Callot esprime con caparbietà fotografica alcune condizioni primarie del “carattere” di personaggi dall’alone “mitologico”, come: Capitan Malagamba a Capitan Bellavita e i loro “Lazii”, Razullo al colascione e Cucurucu alla danza. Ognuno di questi condiziona l’immagine stessa orientandola verso una dimensione di movimento coreutico e spettacolare, senza mai tralasciare quel sentore mitizzato del virtuosismo delle maschere.

Il virtuosismo viene ben evidenziato da uno dei nomi “minori” di questa forma d’arte, la commedia improvvisata; i lazzi, le toccate, i prologhi, le aree, i vezzi, i fracassi, le danze, condizionano movimenti e musicalità dell’attore-musico. Nella “Selva, ovvero Zibaldone di concetti comici”, risalente al XVIII sec., dedicato da Placido Adriani alla Commedia, il canonico descrive alcune condizioni basilari dell’essere maschera, dunque personaggio dell’opera stessa; Adriani inserisce, prima dei prologhi dei canovacci delle commedie, alcuni testi dal carattere strettamente musicale dei quali indica funzionalità e concordanze con i successivi scritti: Aria da cantarsi alla napoletana, Ottava alla toscana, alla romana, stile villanesco. Queste indicazioni, fanno intendere quanto gli stessi attori sapessero rappresentare e interferire con il testo donando caratteristiche estetiche ben differenti a seconda dei canovacci: “Ariose avite, gli occhi, e le ciglia dè signora dell’alma mia cò lò à à à la tieni e non me ne dai cò lò brù brù brù, gli occhi e le ciglia dello pappagallo, ii ii ii.”. L’estetica musicale e l’intersezione lessicale della parte testuale del canovaccio si fusero in un matrimonio artistico capace ancora oggi di testimoniare allo spettatore quella potenzialità artistica senza precedenti.

I testi teatrali dell’epoca riportano solo il testo delle parti da cantare, omettendo completamente qualunque indicazione musicale. Pensare che un prelato del XVIII sec. non avesse conoscenze musicali è cosa ardua; la possibile spiegazione può risultare semplice se si considera la continua e irrefrenabile contaminazione tra mondo colto e tradizione orale che fu prassi comune all’epoca.

I due universi seppero compensarsi, tanto che in alcune edizioni musicali, a partire dal primo Rinascimento, titoli e indicazioni musicali suggerite “risolvono” esteticamente in situazioni dal gusto popolareggiante, a volte direttamente provenienti dalla tradizione orale. Gli attori e la musica sono dunque una stessa cosa; dalla musica sono rappresentati e a loro volta la condizionano: “Vecchio come son recitarò senza ballar con salti smisurati; el minuetto per altro lo farò”; (Sacchi 1786, Genova).

Massimiliano Dragoni

Ascolta un sample – Listen a sample

A notarial act registered by V. Fortuna in Padua in 1545 supports the theory that, in the Commedia dell’Arte, the roles of actor and musician were often filled by one and the same person. This is not surprising, considering that the kinds of virtuosity needed for improvising on a theme or to create an extemporary theatrical situation based on a canovaccio certainly share many characteristics. Fortuna’s text, found in an archival document, is the first known record of the foundation of a company of commedianti, even if there is no reason not to believe that other, similar, artistic troupes existed previously.

Among the artists mentioned, Fortuna indicates Francesco da la Lira, musico-attore e danzerino. This archaic method of identification, where a stage name is created by combining the name of an actor and/or musician with that of their instrument, gives us a basis for a musical and historical study that looks into the inner workings of the Commedia dell’Arte itself. Thanks to this identification by name of the musical instruments, not only do we know what instruments were used, we also have an idea of the kind of aesthetic, taste and dynamic characterization favored during the era of Commedia, that “carnevale italiano mascherato, ove si veggono in figura varie inventione di capritii…” (F. Bertarelli, 1643.)

In addition to the Paduan notarial act, other documents provide precious historical information towards the reconstruction of the practice of the Commedia dell’Arte, for example, the engravings of Callot. The artist’s series dedicated to the theatrical masks of his time (1621-22) is entitled “Balli di Sfessania.” From the first page, the “multi-tasking” ability of the artists of the Commedia is made evident: we see three masked characters on a small stage, dancing to the accompaniment of colascione and tamburello, uniting the three elements music, dance and theater that form the basis of the Commedia.

In his series of representations of personages and movements, Callot manages to portray, with photographic accuracy, some of the hallmarks of the “legendary” figures of the Commedia, such as Capitan Malagamba, Capitan Bellavita and their “Lazii” (comedy routines;) Puliciniello and Lucrezia; Razullo, the colascione player; and Cucurucu, the dancer. Each character conditions the image portraying him, bestowing upon it a dimension of theatrical, choreographic movement that gives us a sense of the legendary virtuosity of the performer. Music becomes a preponderant, creative element of the image itself.

The important role played by virtuosity is reinforced by one of the art form’s lesser-known names: la commedia improvvisata. The Lazzi (gags,) toccate, prologues, arias, vezzi (tricks of the trade,) fracassi (bang-ups,) and dances that make up the performances condition the movements and musicality of the actor/musicians.

“Selva, Zibaldone, ovvero Zibaldone di concetti comici…,” is an 18th century source dedicated to the Commedia. In it, Placido Adriani, a priest from Lucca, aptly describes a few of the basic situations involving characters in maschera. Before his prologue to the canovacci (plot sketches used by the actors as a basis for improvisation) employed in the commedia, Adriani inserts a few texts of an obviously musical character. He indicates their function and models with titles like Aria da cantarsi alla napoletana, Ottava alla toscana o alla romana, or stile villanesco. These names underline to what degree the actors were capable of acting out or manipulating the texts, depending on the demands of the canovacci, giving each one a different aesthetic character that was easily identifiable by the public of the era: “Ariose avite, gli occhi, e le ciglia dè signora dell’alma mia cò lò à à à la tieni e non me ne dai cò lò brù brù brù, gli occhi e le ciglia dello pappagallo, ii ii ii.”. (P.Adriani).

Aesthetic and musical considerations, and the lexical richness of the canovaccio texts blend together in an artistic marriage still capable of giving us a sense of the unprecedented artistic force of the era.

In the sung sections of Adriani’s collection, only the song lyrics are written down. In other words, musical notation is completely absent from the theatrical text. It would be hard to imagine that this was because the author was incapable of writing music it is almost impossible that an 18th century prelate would not have had some kind of musical training. A possible explanation for this surprising lack of musical notation is the irrepressible, constant contamination between the cultured sphere and the oral tradition of the era, that would have made it unnecessary to write down tunes that everyone, including an educated priest, would have known by heart.

In fact, the two universes balanced each other out to such a point that, in editions from the early Renaissance, certain pieces have titles or musical indications, as well as a “popular-style” aesthetic that point to material coming directly from the oral tradition. At the same time, we have evidence of a “trickle down” effect: the use of some of the “greatest hits” of the era, taken from the famous written collections of canzonette, strambotti and frottole, in “popular” situations where it would be all but impossible that the musicians would be playing from written parts. It’s true that, if some pieces take their name directly from some of the masked characters of the Commedia, probably because of their identification with a particular dance or comedy routine, some of the melodies are similar to ones still heard today in the popular tradition, in music for carnival or other archaic celebrations or rituals. The actors and music, in every sense, are one and the same: they are portrayed by the music at the same time as, in playing, they transform it: “Vecchio come son recitarò senza ballar con salti smisurati; el minuetto per altro lo farò”; (Sacchi 1786, Genova).

Massimiliano Dragoni (traduzione di Avery Gosfield)

Per info o acquisto / For info or to buyEmail: maxre@maxresearch.comSull’email indicare nome e codice prodotto, e il motivo del contatto.GrazieOn email indicating name and product code, and a contact reason.Thank youDownload sample audio HD 24bit 96KHZ Max Research productionDownload sample audio Max Research production | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

D5 Creation

D5 Creation